“Men, Emotions & Masculinity: The Quiet Revolution in Group Therapy”

Author - Sakshi Lal

Year Published: 2024

Introduction

A recent survey by Bartle Bogle Hegarty in 2022 has shown that there is an overwhelming expectation of resilience amongst men in Singapore (Ang, 2022). Singaporean men are prevented from seeking help for their mental health issues as men are expected to be more emotionally resilient than women. 73 per cent of men are not seeking help due to a fear of loss of respect from their peers. Traditionally, masculinity does not encourage men to express their emotions like crying and men will want to hide and suppress their emotions. The article describes how we have been. They are expected to appear strong, stoic and emotionally resilient. But emotional resilience is not about repressing one’s emotions but embracing them fully and turning to support to help. This bottling up of emotions of men who are mentally struggling must stop before it is too late. Thus, the importance of looking at how to help men understand and articulate their emotions becomes critical, with group therapy being a promising modality. Given the paucity of literature on psychoeducation, counselling, or self-awareness groups on this specific issue, we arrived upon support groups as offering the greatest flexibility to account for the diversity experiences that men encounter when exploring this issue.

Literature Review

An overview of the literature reinforces the need to normalize and support men’s socio-emotional needs. Men from different age groups and socio-economic backgrounds are reluctant to seek help and disclose emotional distress due to conditioning and being exposed to traditional masculine norms (Courtenay, 2000). That continues to cause a higher rate of alcohol, substance abuse and suicides (ONS, 2020).

However, studies show that men are willing and able to discuss emotional difficulties under the right circumstances. As men may not always have the option to disclose emotional distress to family, friends or colleagues, and as per Seidler et al. (2020) men may find the traditional one-one therapy not very male friendly, they do benefit from attending support groups in the following ways:

Shared experiences: Men found a sense of belonging and understanding in a support group where they could find people who have similar experiences and emotions which created “shared-ownership” and resulted in improved mental well-being (Thoits, 2011a).

Safe space: The confidentiality and absence of personal ties to others in support groups minimizes any potential threat to the member’s masculine identity which in turn facilitates men’s participation. Men have reported that they do not feel the need to maintain a certain set of masculine norms that limit emotional expression at support groups unlike at home where they are playing the role of the major bread-winner of the house or at workplace where they are supposed to play and maintain a masculine identity (Courtenay, 2000).

Tailored support: As men meet other men with specific issues like a common illness, example cancer or a mental health difficulty like depression, anxiety or isolation, support groups provide an opportunity for them to come together and share specialized knowledge and experiences on how to cope and provide specific support (Gage, 2013). Men by receiving and providing support to each other find a sense of purpose to support other men and in the process reconstruct masculine identities (Creighton & Oliffe, 2010).

Social benefits: Support groups provide opportunities to build social and friendship networks to discover new or common interests thereby reducing social isolation and decreasing symptoms of distress.

This is reinforced by Wexler in his book Men in therapy: New approaches for effective treatment, “Men’s therapy groups are able to deepen men’s experiences and open up possibilities for self-examination.” (Wexler, 2009, p. 199) Wexler argues that the men’s group encourages norms around feelings and vulnerability, which is particularly salient for working with men for whom emotional expression might be difficult (Wexler, 2009, p.199).

Through the norming of behaviours such as “Talking about feelings, speaking respectfully about women, taking personal responsibility for mistakes, not letting circumstances dictate personal responses, and even shedding a few tears” (Wexler, 2009, p.200), Wexler argues that men’s groups allow their participants to expand the definition of what acceptable masculine behaviour looks like, something of particular import given how men are traditionally socialized in many cultures.

Furthermore, Wexler emphasizes the power of men’s groups in allowing for shared discussion of taboo topics, such as fears around declining sexual performance, fear around death and aging, and disappointment around unrealized dreams (Wexler, 2009, p.202). Providing a space for these emotionally charged but often socially forbidden topics allows for the normalization of these topics, rather than men feeling as though these issues were “personal attacks on their masculinity.” (Wexler, 2009, p.202) Encouraging emotional vulnerability around these issues also models to men that if the most shameful issues are open for discussion, other issues in their life are as well.

Wexler does caution against potential issues that could arise within a men’s group. Competition for attention, approval, and social status might overshadow the initial intentions of the group. (Wexler, 2009, p.212) Furthermore, embittered men might leverage the group setting to lure men who might only be marginally embittered to their side. It is the group leader’s responsibility to ensure that the group stays the course, and to address potential detractors and their concerns.

Furthermore, a study conducted from 2018 to January 2019 involved interviews with a group of seven men aged 28 to 54, who had completed a 14-session group Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) program at three outpatient mental health centers in Denmark (Bryde Christensen et al., 2023). The therapy was divided into diagnosis-specific groups for conditions such as depression, panic disorder/agoraphobia, and social phobia, as well as transdiagnostic groups for depression and anxiety, based on the Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders.

The men's reflections on their therapy experiences contrasted with traditional masculinity norms, which emphasize autonomy and self-reliance. Instead, they described a sense of unity in their group, formed through shared experiences. For instance, one participant, Marcus, noted he initially felt isolated in his anxiety but realized that many others in the group had similar feelings. Another participant, Peter, elaborated on the personal impact of recognizing his experiences in those of other group members.

Peter discussed how participating in group therapy positively impacted his self-esteem by highlighting that struggles with psychological issues are common and not indicative of being a "bad person." He metaphorically describes this as lightening one’s emotional burden, leading to a greater sense of ease. The men in the group found solace in recognizing their shared experiences, contributing to the normalization of psychological suffering. Marcus noted that discovering his feelings of unreality were not unique alleviated his distress, while Peter emphasized the shift from feeling like an outsider to feeling "completely normal" within the group.

The findings align with previous research that suggests group therapy can help de-stigmatize psychological suffering among men. Although the men initially resisted the idea of "just talking about it," they found value in sharing their experiences, suggesting that such "passive talking therapy" may be beneficial despite traditional gender norms that typically discourage emotional openness. The construction of a shared group identity allowed for emotional sharing that transcended individual and gender differences, highlighting the therapeutic power of communal experiences.

With regards to suicide rates, there is an assumption that men do not ask for help during psychological distress (Keohane & Richardson, 2018). A study was done to investigate how masculine norms impact men’s help-seeking as well as care givers’ behaviours and willingness to support men in need of psychological help or perceived to be at risk of suicide. The study confirm that male suicide prevention strategies need to tackle with root causes of disconnection of social institution such as family, friends, community. The three themes identified were “negotiating ways to ask for, offer, and accept help without compromising masculinity”. “Making and sustaining contact with men in psychological stresses”, and “navigating roles responsibilities and boundaries to support men in psychological stresses”. To reach a suicide prevention intervention, help-seeking intersection is importation and opportunities to seek more dynamic approach like help-seeking/ giving/taking behaviours. Key interventions look for multiple and complex ways in help seeking rather than one dimensional.

Jansen describes how in her 10 years as a psychotherapist working with men, she notes different themes that have arisen in working with men’s support groups (Jansen, 2020). The themes are 1) Celebrating men as fully human as alexithymia does not mean that men do not experiences human emotions as do not give themselves opportunity to express soft emotions like empathy, joy, sadness and love. 2) Male vulnerability 3) centralizing personhood; not a diagnosis 4) men as moral beings 5) peer-centred men’s group and 6) explicit gender framework. As a gender culture with its own worldviews and values, they are responded to in a gender-sensitive and gender-consistent manner. Their emotion regulation strategies and expressions of gendered subcultural norms are taken seriously. Frequent jokes and raucous verbal sparring are not uncommon as they harmonise the tensions that build up during powerful emotional work.

Content

While there are few strict recommendations on what content should be included in support groups targeting emotional literacy in men, several themes are prominently repeated. Jansen (2020) notes the following considerations as being crucial to the success of any men’s group.

1. Celebrating men as fully human

2. Male vulnerability

3. Centralising personhood, not a diagnosis

4. Men as moral beings

5. The peer-centred men’s group

6. Centering an explicit gender framework

Keohane & Richardson (2018), in their research on how best to support men in need of psychological help also identify the themes of “negotiating ways to ask for, offer and accept help without compromising masculinity”; “making and sustaining contact with men in psychological distress”; and “navigating roles, responsibilities and boundaries to support men in psychological distress.” as being crucial considerations in accounting for the sociocultural context of men’s experiences.

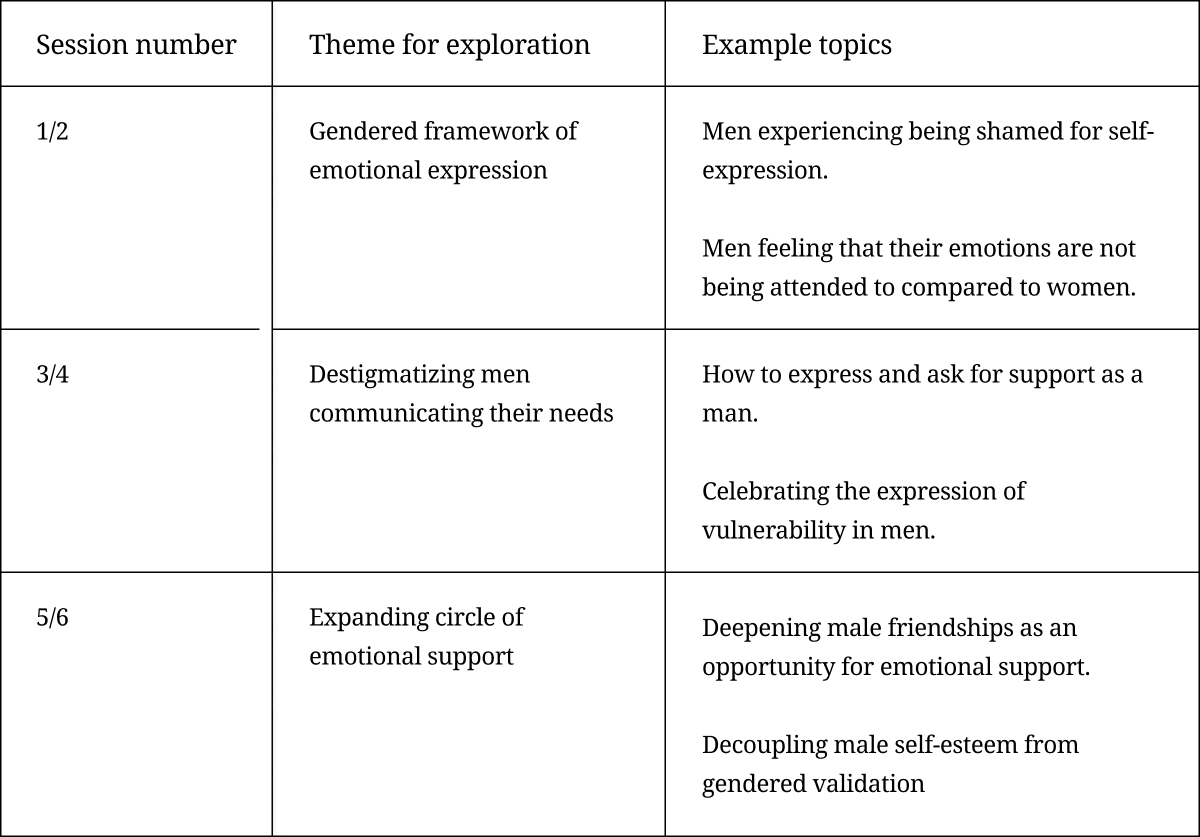

A potential format for a men’s support group that helps them to expand their skills in emotional expression could appear as follows. The sessions would be arranged in ascending order of vulnerability for the participants.

Conclusion

Traditional masculine norms have long hindered men from seeking help for mental health issues, as societal expectations often compel men to display emotional resilience. Recent research demonstrates that these norms can be effectively challenged via Support groups, that provide men with a unique environment for emotional expression, shared experiences, and the development of a sense of unity. These groups facilitate a reconstruction of masculine identities by promoting openness and mental well-being, which is crucial in overcoming the limitations imposed by traditional gender norms (Courtenay, 2000; Creighton & Oliffe, 2010).

Addressing male psychological distress and preventing suicide necessitates a dynamic approach that acknowledges the complexities of help-seeking behaviors. Effective interventions must be gender-sensitive, recognizing men's emotional competence while offering supportive environments that do not undermine their masculinity (Keohane & Richardson, 2018; Jasen, 2020).

Wexler (2009) further highlights the therapeutic value of men’s groups in expanding the norms of masculine behavior. These groups create a space for discussing taboo topics, encouraging emotional vulnerability, and fostering personal growth. Overall, these findings underscore that providing men with appropriate support structures can significantly improve their emotional well-being and facilitate a more inclusive understanding of masculinity.

Reference

Ang, M. (2022, November 22). Men in Singapore find it harder to seek help for mental health due to societal expectations. Yahoo News.

https://sg.news.yahoo.com/men-in-singapore-harder-to-seek-help-for-mental-health-045037606.html

Bryde Christensen, A., Krohn, S., Høj, M., Poulsen, S., Reinholt, N., & Arnfred, S. (2023). “Men are not raised to share feelings” Exploring Male Patients’ Discourses on Participating in Group Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy. The Journal of Men’s Studies, 31(1), 3–24.

https://doi.org/10.1177/10608265221077298

Courtenay, W. H. (2000). Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science & Medicine, 50(10), 1385–1401.

Creighton, G., & Oliffe, J. L. (2010). Theorising masculinities and men’s health: A brief history with a view to practice. Health Sociology Review, 19(4), 409–418.

https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2010.19.4.409

Gage, E. A. (2013). Social networks of experientially similar others: Formation, activation, and consequences of network ties on the health care experience. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 95, 43–51.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.09.001

Jansen, S. (2020). Men are emotionally competent: Considerations on group therapy with men. South African Journal of Psychology, 50, 154–157.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246319854360

Keohane, A., & Richardson, N. (2018). Negotiating Gender Norms to Support Men in Psychological Distress. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988317733093

Oliffe, J. L., Rossnagel, E., Seidler, Z. E., Kealy, D., Ogrodniczuk, J. S., & Rice, S. M. (2019). Men’s depression and suicide. Current Psychiatry Reports, 21(10), 1–6.

Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161.

Seidler, Z., Rice, S., Kealy, D., Oliffe, J., & Ogrodniczuk, J. (2020). Getting them through the door: A survey of men’s facilitators for seeking mental health treatment. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 1346–1351.

Statistics, O. for N. (2020). Suicides in the UK: 2019 Registrations, Statistical Bulletin.

Vickery, A. (2022). ‘It’s made me feel less isolated because there are other people who are experiencing the same or very similar to you’: Men’s experiences of using mental health support groups. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), 2383–2391.

https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13788

Wexler, D. B. (2009). Men in therapy: New approaches for effective treatment. WW Norton & Company.

Related posts

“Men, Emotions & Masculinity: The Quiet Revolution in Group Therapy”

A recent survey by Bartle Bogle Hegarty in 2022 has shown that there is an overwhelming expectation of resilience amongst men in Singapore (Ang, 2022)

Effectiveness of SFBT in Reducing Workplace Stress and Burnout in Employees

General workplace stress levels have increased by over 20% in the last three decades (Korn Ferry, 2019) and 1 in 5 employees spend at least 1 hour contemplating their stress weekly in the Canadian workplace (Statista, 2021).